Learning about mental illness, from flies!

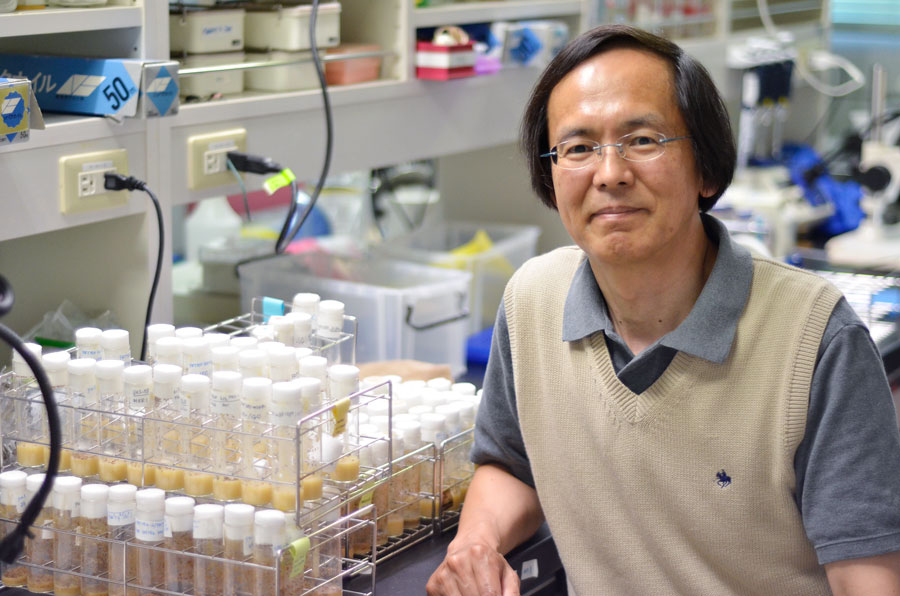

In a small, cramped laboratory crowded with incubators and racks of glass vials full of fruit flies, graduate students sit at benches routinely shaking flies into fresh vials, and sorting males from females under a microscope. It seems an unlikely setting for the next breakthrough in understanding mental illness, but Katsuo Furukubo-Tokunaga would argue the opposite. Based at the University of Tsukuba, Japan, he is one of a growing network of researchers in the fledgling field of psychogenetics, who believe that established genetic techniques for Drosophila melanogaster can help uncover the causal mechanisms of diseases such as schizophrenia, autism, and bipolar disorder.

Furukubo-Tokunaga began studying the genetic formation of the fly brain 20 years ago. At that time the genetic mechanism of brain development was virtually unknown, and the fly brain provided a relatively simple model for investigating the fundamental processes through which a neural network is constructed. The ultimate goal back then was to understand how the brain controls behavior. Tantalizing evidence from studies of twins had suggested that genes play a significant role in determining behavior (up to 40%). So it was thought that if genes control behavior, the mechanism might be through the original wiring of the brain during development.

Since then, the sequencing of the human genome has opened the way for a genetic approach to psychiatric disease research through genome association studies. Searching for common genes, patterns of genes, or patterns of damage to genes among psychiatric patients allows identification of risk factor genes, the presence of which increases the likelihood of developing a mental illness. Thanks to studies of this type, known risk factor genes now number in the hundreds, but the main question of how these genes manifest in disease is still unknown. “There is still a ‘black box’ between the genes and the disease,” laments Furukubo-Tokunaga. So with his background investigating behavior as a product of brain development under the direction of genes, it seemed a small leap to approaching mental illness (as aberrant behavior) in a similar way.

Drosophila melanogaster has been the poster child for genetic research for more than 100 years, and for good reason. Fruit flies have a relatively short, fully sequenced genome, they breed and grow quickly and are easy to keep in the lab. And importantly, they are a lot like us. Although flies and humans are very distinct from each other in appearance, 70-80% of genes are conserved between them.

Furukubo-Tokunaga’s research focuses on a gene called DISC1 (Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1), the corresponding protein of which is located in various parts of the cell and appears to be involved in several important neural processes such as synaptic transmission and network formation. DISC1 is a highly potent risk factor gene for diverse mental disorders including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and autism. Studies in flies have begun to reveal associations between mutated forms of the DISC1 gene, altered localization of DISC1 proteins, and unusual activity of transcription factors; along with endophenotypes (the biological alterations underlying psychiatric symptoms) such as mutated neuron structure; and behavioral symptoms like disrupted sleep patterns, inhibited learning, and attention deficiency.

Connecting symptoms to genes and endophenotypes is hoped to offer new objective tools for the diagnosis of mental disorders, which currently relies almost exclusively on subjective patient interviews. Eventually, researchers hope to uncover a continuous link from genes all the way to the diseases they cause.

But mental illness is not likely to be caused by a single gene. Rather, it is more likely to be a combination of risk factor genes interacting with each other that bring on the disease. Unraveling this complex interaction is another challenge on the road to understanding mental illness, and one to which the fly model is again thought to be well suited. The relative ease and speed with which multiple gene mutants can be produced in flies should give them an advantage over other animal models for screening and investigating combinations of multiple risk factor genes.

Of course there are limits to what can be learned about human mental illness from studying fruit flies—at some point these studies will be limited by the simplicity of the fly brain. But for now, Furukubo-Tokunaga argues, it is precisely that simplicity that is the fly’s advantage—by offering a relatively simple model for investigating the molecular and cellular impacts of human risk factor genes, and revealing fundamental steps on the path from gene to disease.

Let me tell You a sad story ! There are no comments yet, but You can be first one to comment this article.

Write a comment